What’s in a name?

One of the most exciting steps for family historians is discovering the original meaning of a surname, or how it came to be. Finding out a little about the very first progenitor of a family name can often be interesting, particularly for fellow family members. Surnames also continue to be a topic of interest to historical researchers, and British surnames have been the subject of numerous investigative efforts and catalogues over the years. British surnames can typically be classed into four different types. For the vast majority of such names, the original meaning has been evaluated and published, although some tricky names present a more difficult problem and are perhaps even subject to continuing debate. This article will explore classic British surnames, ie. names which came about in Britain during the Middle Ages. Names deriving from later global interactions and periods of migration falls outside the scope of this article. Here are the four main surname groups: What type is yours?

1. Patronymic

The most popular way of finding a surname in the Middle Ages was by taking the fathers name as an identifying name for the family, a patronymic. On a basic level this involved a son or daughter apending the fathers name to their own. In some more unusual cases, a person might take their mothers name as their last for instance Hester or Alice.

The use of patronymic surnames differed between the constituent countries of the British Isles.

In England, the convention was to pluralise the fathers name as a patronymic, such as Rogers. This name would thereafter remain fixed for each successive generation. The relative ease of pronunciation ultimately determined how a name would eventually sound. Jones is certainly easier to say than Johns. Jones is ultimately the UK’s most common surname, because John was by far the most popular male name in England over hundreds of years. Other examples of English patronymics include Williams and Davis.

The Old Norse naming style was for the son to take their fathers name as a second identifier, involving the fathers name with the addition of son after, for instance Bjorn Ragnarson. Women would be given a matronymic, and use the first name of their mother as their second name. This method lead to a different surname for each generation. The Vikings conquered large parts of England, and in areas under their control, this tradition continued past the end of the Viking era, leading to the development of names such as Johnson and Davison.

In the Norman naming tradition, patronymics would often be used to identify family relationships. A son would be known by his father’s Christian name, with use of the suffix ‘Fitz’ a Norman corruption of the Latin ‘fils’, meaning ‘son of’. Fitzroy, as ‘son of the king’ would have been the surname for a royal bastard. The Normans invaded Ireland, introducing Norman names there. Such names were eventually fixed in the Middle Ages and thereafter remained static. Surviving examples include Fitzgerald and Fitzpatrick, which are both associated mostly with Ireland.

In Wales, the patronymic tradition was followed throughout the Middle Ages, with a similar pattern to the Norman style. In Welsh, ‘Ap’ meant ‘son of’, so Owain ap Rhys might have been a son of Rhys ap Harry. Following increased English influence in Wales, Welsh surnames eventually fixed to match the English tradition. Distinctive Welsh names often begin with a ‘p’ due to the abbreviation of ‘ap’, leading to names such as Price and Parry following the example above.

In Scotland, people were named after the clan they belonged to. The origin of the Scottish clan derived from Mc or Mac, Gaelic for son of. Some examples include the famous clans of McKenzie and MacDonald. Clans did not exist along purely

2. Geographical

Geographical names are the second most common after patronymics. If someone didn’t want to take their father’s name as their own, they might instead have to describe themselves by their place of abode or where they came from originally. The wide variety of possible landmarks lead to the emergence of many different geographic names. Many of the most popular were short and to the point. Examples include Hill, Mill, Hall, Lane, Wood, Orchard, Berry, Brooke, Lee and Combe. A variant of the geographic name was the combination of a place with a direction, such as with Underhill, Underwood. Such direction might have proved useful at the time, but such directions are far too vague to have any hope of pinning down a specific location today!

3. Locational

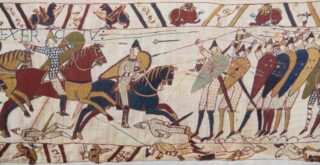

Locational names are much like geographic names but refer to the name of a specific place rather than the description of a locality. They derive from the name of a village, parish or specific property. This could be either a place of current residence, or where the individual was from originally. The Norman knights who participated in the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 took their names from their chief residence in Normandy. The Mortimers name was from the small village and castle of Mortemer in the Pays de Brays region of Normandy. Other Norman knightly families included the Warennes, de Clares, and de Veres, who gained hereditary Earldoms in England. Later in the Middle Ages, landowning lords of the manor would derive their name from their parish of residence. Evidence of this tradition can be seen in Gloucestershire, where existence of the Cam, Cowley, Stinchcombe and Slimbridge families shows a clear pattern for assuming the name of the manor in their possession.

4. Characteristic

Characteristic names derive from a description of the very first person to bear the name, and are the rarest type of British surname. This could have been a description of the persons appearance, like Black- someone with dark hair, or Armstrong- a stocky and well built person! Of course if someone was old and graying they might have been described as grey, or even white! Other interesting Characteristic names include Savage, Shakespeare and Ironside.

A note on the permanence of surnames

Many unique British surnames have disappeared altogether from the British Isles over the years. These include ‘Chips’ and ‘Foothead’. Some names today are also rare and in danger of disappearing. The First World War caused the extinction of a number of English surnames, as the fighting caused the decimation of an entire generation of young men. Some very rare surnames were isolated to individual villages, and therefore simply died out.

Alias names

Alias names were created when someone took on two different surnames simultaneously, being known by either or both throughout their lifetime! Find out more here.

Recent Comments