Early life

My fourth great grandfather was William Mortimore. Both his origins and early life are obscure, but two facts of his life are known. He was probably born into the lower rung of society, and he moved to Bristol for work during the employment troubles caused by the industrial revolution. By trade he was variously described as either a milkman or labourer, and he was perhaps a labourer in a dairy. He moved to Bristol before the age of 30, marrying twice and fathering eleven children. The earliest sign of his arrival in Bristol was his marriage to Jane Moody, a spinster from Wiltshire, on 22 Nov 1819, in the parish of St James Bristol. William was aged over 30 and Jane was aged 22. Both were illiterate and used a mark to sign their names. The register recorded neither their ages nor occupations and no family members attended as witnesses, making it a challenge to trace their families. Both were born in neighbouring counties and had moved to Bristol from the countryside. Jane was born in Nov 1797, North Bradley, near Trowbridge, Wiltshire, where coincidentally, an unrelated Mortimer family also lived, derived from the Mortimers of Wiltshire.

Marriage record of William Mortimore and Jane Moody, 1819

View of Bristol from Clifton, c. late 18th century

Marriage to Jane Moody

Bristol St James fair in its hay-day

William and Jane exchanged marriage vows at the parish church of St James, Bristol. The church was originally built as a Benedictine Priory in the 12th century, and became the location of a popular annual fair from 1374. The fair was held in St James’ churchyard, and spilled into the surrounding streets, providing entertainment and merry making for many. In the early 1800’s the fair had become so popular that merchants planned their shipping routes around the fair to supply luxury goods like wine, dyes and exotic fruits or oils.

By the time of William and Jane’s marriage in 1819 the fair had gathered a reputation for frivolous merry making that was in stark contrast to the ideals of the original founding monks! Certain characters of ill repute were said to stalk the streets eager to corrupt the young to a life of low morals. Strident objections from the religious community eventually lead to the fair being banned in 1837. Luckily St James church was one of the few medieval churches that survived the Bristol Blitz largely unscathed and is the oldest building in Bristol to survive near to its original form. After the war it fell into disuse but was eventually saved and restored.

Bristol St James Priory, West Front

Life in Bristol

William Mortimer arrived at a time of great change in Bristol. Across the skyline, the ancient buildings of the medieval city were being demolished to make way for the new architecture of Empire and prestige. Wealthy merchants and financiers, some of whom had made their fortune in the slave trade, wanted to live in modern housing with style and opulence. Whilst the splendid medieval merchant houses of Bristol had previously been a sign of wealth and privilege, by the 1800s these antiquated buildings had lost their appeal and turned into slums, becoming a magnet for disease and malnourishment. The majority of these ancient buildings were home to the poorest of Bristol society, and those who lived there had no other choice. Bristol antiquarians managed to commission engravings of many such buildings before they were lost to history, with some illustrations completed just as the buildings were being pulled down.

Old house on Temple St, Bristol

Lewins Mead, Singular Buildings

House on Bristol Back, demolished 1818

Old house on Baldwin St, demolished 1823

Demolition of an old house on Wine St., c.1820s.

Family life in Bristol and Bedminster

William and Jane had four children together. Their first child was born 2 years after their marriage.

- John Edward, bap. 29 Apr 1822 Bristol St James

- Matilda, bap. 27 Oct 1822 Bedminster St John the Baptist & Bristol St James

- Mary Ann, b. 9 Jul 1827, bap. 17 Jan 1841 Bristol St Philip & St Jacob

- James Mortimer, b. c.1833, bap. 17 Jan 1841 Bristol St Philip & St Jacob

After 1822 William and Jane stopped baptising their newborn children, presumably after lapsing into non-religious observance. By 1822 they had moved to Upper Knowle, where their daughters Matilda, Mary Ann and second son James were born. Although it was required to baptise children in the parish where they were born, Mary and James weren’t baptised until 1841. They might even have had more children who did not survive. At this point Upper Knowle would have been at the fringes of the city, as the industrial success of Bristol attracted migrants from rural areas, forcing expansion. By the 1830’s the population had grown over 10 fold since medieval times, the overwhelming majority of the population boom occurring from the industrial revolution.

Antique map of Bristol, 1797

Unrest in Bristol

William Mortimer and his family lived during a time of great social change. Bristol was a fast growing industrial town, but was still not given the political representation it deserved. Aside from this, only 6 out of 100 Bristolians had the rights to vote. The 1831 Reform Bill which aimed to get rid Parliament of the rotten boroughs and give industrial cities like Bristol greater representation, was defeated in the House of Lords, leading to bitter resentment.

When the local magistrate arrived to open the new assize courts in Bristol, anger towards the establishment boiled over. An angry mob attacked and chased the magistrate to the Mansion House in Queen’s Square, and hundreds of people began rioting. The rioters set fire to several important public buildings, also destroying the Bishop’s Palace and setting free the prisoners from Bristol gaol. The Dragoon Guards were called in to restore order and shot at the rioters to disperse the crowds. Four rioters were killed in the ensuing melee, and several soldiers injured. The city must have seemed akin to something like a way zone, as fighting erupted in the streets and further fires were started.

Queen Square Riots, Bristol 1831

Dragoons open fire on the Bristol Rioters, contemporary illustration

Bristol conflagration on the night of the Queen Square riots, 1831

The fires of Bristol blazed throughout the city centre, and could be seen from many miles away. Many unfortunate residents perished in the inferno, which continued to rage through the night. The following day, Bristol residents were greeted with a scene of devastation, as the Mansion House, Bishop’s Palace and many other buildings on Queen Square were gutted and destroyed. A thick layer of ash fell like snow on the city, and the fire service worked hard to extinguish any remaining small fires. The repercussions of the riots were severe. 114 people were convicted of rioting, of which 31 were executed. The commander of the Dragoons was court martialled for leniency, having ordered the 14th Light Dragoons away from the riots during the heat of the action. He later committed suicide before his trial.

Queen Square, Bristol, the morning after the riots, 1831

Tragedy strikes, 1834

Temple church, Bristol, antique engraving

Second marriage

Marriage record of William Mortimore and Mary Ann Tippins, 1835

- Jane, b. 1836, bap. 14 Feb 1836 Bristol St James

- Mary Jane, b. 1838, bap. 18 Nov 1838 Bristol St James

- Sarah Jane, b. 17 Mar 1842, bap. 10 Apr 1842 Bristol St Philip & St Jacob

- Elizabeth, b. 30 Nov 1844, bap. 25 Dec 1844 Bristol St Philip & St Jacob

- William, b. 1850, bap 10 Aug 1850 Bristol St Philip & St Jacob, d. Mar 1851 Bedminster

While devoted to his younger wife Mary Ann, William obviously cherished the memory of Jane, as he continued to name three of his daughters after her. The family were living at 7 Pipe Lane, Bristol Temple by 1838, when Mary Jane was born. Her birth record showed William worked as a milkman. Their eldest child Jane did not survive, as Mary Jane was known just by her middle name until her marriage. Although the children were born south of the river, William and Mary continued to cross the river to baptise their children at St James and then St Philip & St Jacob parish church. Mary Ann and James, children by his earlier marriage to Jane, were both baptised on 17 Jan 1841, they were aged 13 and 8 respectively.

St Philip and St Jacob church, Bristol, from antique engraving

No further happiness – for all hope dies

Though William lost his wife in 1834, his fortunes were sadly not to improve. Both William and his family would have to endure even further heartbreak, that would break even the most tight knit of families. For in 1838 and 1840, the unimaginable happened. Both William’s eldest children, his son John Edward Mortimer and his daughter Matilda, died before their eighteenth birthdays, killed by the hideous diseases that continued to ravage industrial cities. Matilda was doubtless loved by all her siblings, and in the death of poor John, young James no longer had an older brother to look up to. William must have been devastated, for he had always hoped that in his eldest son, his line would continue, and in time his children would be both safe and prosperous. No man could ever recover from such a loss, and William was left a broken stranger to all.

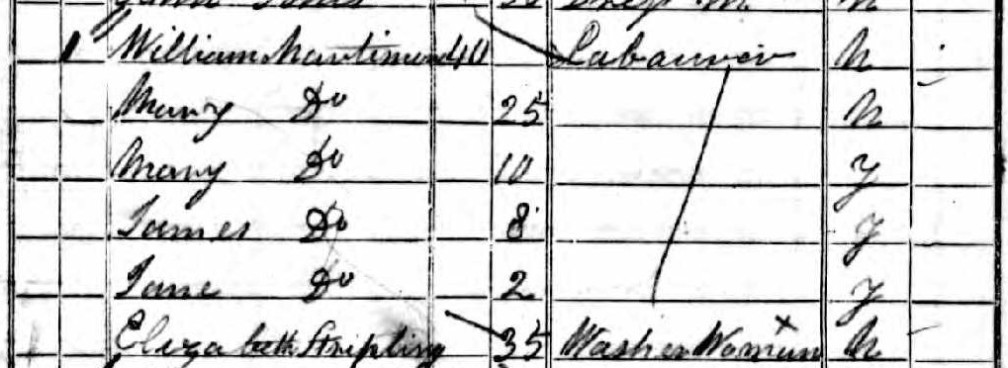

Household in 1841

The Mortimer family, or those who had survived the devastating sickness outbreaks of the 1830’s, continued to live in Bristol, for by then they had no other choice. The year after Matilda’s death, the Mortimers lived in Pipe Lane, Bristol. The first national census was carried out in June 1841. Whilst it is not entirely clear exactly where Pipe lane was, it should not be confused with Pipe Lane, St Augustine parish, which is closer to the city centre. Bristol Temple parish was south of the river Avon and originally in Somerset, but was incorporated into Gloucestershire as part of boundary changes, along with the rest of Bristol city registration district. In the census the family members’ ages were rounded down to the nearest five years and the relationships between the family members were not stated, though the head of the house was written first.

The Mortimer household in 1841 – census record

The 1841 census imparted limited but interesting information about the household. William and Mary were both born outside Bristol, while the children were all born in the Bristol area. William worked as a labourer, but only a few years before in 1838 he had been termed a milkman. He either laboured in a dairy, or his milk and dairy work was equivalent to that of a labourer. Both Mary and James were probably working at the time, for the family had lost the income of both John and Matilda Mortimer. It wasn’t until 1876 that school attendance was made compulsory, and the young children of the family’s experience of school would probably have been very limited. James might have received only some schooling, for he was able to sign his name in 1862. Elizabeth Stripling, a washer woman, also lived with the Mortimers in 1841 but was unrelated to the family. Elizabeth was born c.1805 in Minehead, Somerset. It was common for people to cohabit at the time, and many poorer families had to share lodgings. The family probably lived all on one floor of a house.

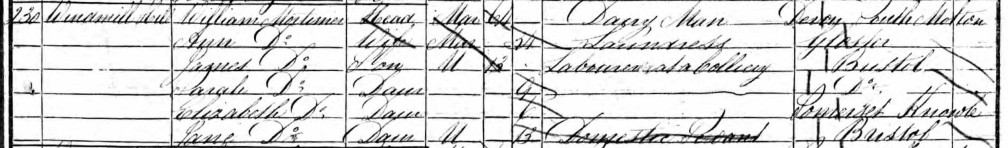

The Mortimer household in 1851 – census record

Oddly, William seems to have aged 24 years in just a decade, reflecting the inaccuracy of the census ages! Here is evidence that there was at least a 30 year gap between William and Mary Ann. James Mortimer is recorded in the household, even though he was no longer living with them, having moved to live with his step uncle George Tippins in the Forest of Dean and work as a colliery labourer.

Marital separation and family breakdown

By this point the once close Mortimer family had begun to drift apart, with Mary Ann, William’s eldest daughter, moving to live with Charles James, having a daughter seven years before their marriage in 1852 and James, the only surviving son, moving to the Forest of Dean to live with his Tippins relatives. Sometime between 1851 and 1853, William and Mary Ann separated. What followed the separation though was extraordinary. Mary Ann moved back to the Forest of Dean, taking Elizabeth, her youngest daughter with her. It was there that she remarried in 1853 to Thomas Beach. Whether they had been having an illicit affair and promised to run away together is unknown but it is an interesting thought. Not only that, but William Mortimer was still alive. This was unashamed bigamy at its most blatant and a flagrant violation of Victorian moral values. Thomas and Mary were also breaking the law. Their bigamous marriage was carried out four years before the 1858 Matrimonial Causes Act which legalised divorce through the civil courts.

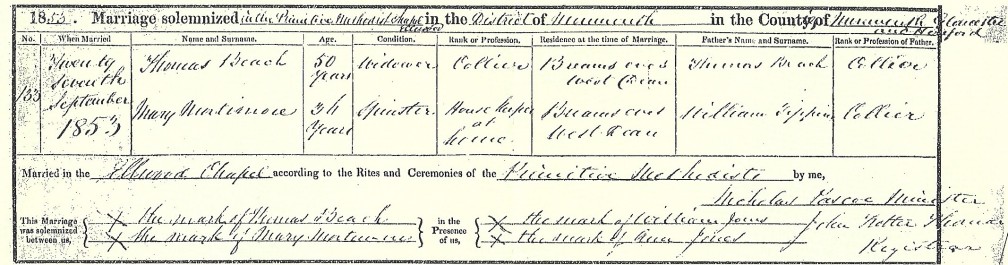

Mary Ann Tippins second marriage – bigamy!

In this context it is surprising that Mary Ann made no attempts to even conceal her identity or change her name before marrying Thomas. The marriage record follows:

Thomas Beach and Mary Mortimore marriage record

27 Sep 1853, marriage solemnized in the Methodist Chapel of Elwood, Monmouthshire.

Groom: Thomas Beach, age 50, widower, Collier, Breams Eaves West Dean, father: Thomas Beach, collier.

Bride: Mary Mortimore, age 36, spinster, housekeeper at home, Breams Eaves West Dean, father: William Tippins, collier.

Both bride and groom signed their names with a mark (X). The marriage was performed by Nicholas Pascoe and witnessed by William and Ann Jones, who were clearly friends of the couple. Both also signed with a mark. At first glance, there is nothing unusual about the marriage. The couple were from the same area with a similar social background, less than a generation’s age gap between them. Both their fathers worked as colliers in the Forest of Dean. The bride, groom and witnessed all signed with a mark, reflecting the low rate of literacy in the area. What is striking is that Mary stated her status was a spinster, meaning an unmarried woman, yet as her father is William Tippins, Mortimer is clearly not her maiden name. She must have been married or widowed herself and her only grounds for marriage being as a widow, like her fiancee Thomas Beach, yet this detail seems to have passed unnoticed. She presumably pretended that she was an illegitimate daughter of William Tippins by a woman called Mortimer. It is clear why they married far away from Bristol, so to limit the chance of objections to their impending marriage.

Family migrations

In 1861 we find the happily wedded couple living together in Whitecroft, near to where Mary Ann was born herself. Interestingly, her daughter Elizabeth’s name had changed to Elizabeth M Beach, to reflect her new marital status. Presumably the M stood for Mortimer, reflecting her real maiden name. Why Mary Ann Tippins moved from West Dean to Bristol, only to move back again 18 years later and marry Thomas Beach is a mystery and one that will probably never be answered! Being a family of very little substance, they left nothing of value to be handed down the generations that might have enlightened their lives. Eventually all but one of William Mortimer’s surviving children joined her in the forest of Dean, including Mary Ann, James, Mary Jane and Elizabeth. Perhaps they sympathised with Mary Ann’s side. Sarah Jane married and stayed in the Bedminster area before emigrating with her husband to Tuscarawas, Ohio, USA. Mary Ann Beach died in 1370 and was buried 13 Apr 1870 Parkend St Paul church.

Final years

William Mortimore stayed in Bristol but moved to 41 St Thomas St, in the parish of St Thomas Church. Before 1861 he was invalidated and forced to retire. In 1861, William was into old age and approaching the end of his life. At the census, his age was stated as 68 but he was likely older. With none of his family around to care for him, he finally perished of Bronchitis in 1862. Ellen James was present at his deathbed, although she was likely a servant of no connection to Charles James who married his eldest daughter Mary Ann Mortimer. With no possessions or property to speak of, William made no will and there is no record of administration after his death. He was likely buried in the cemetery of Arnos Vale near Totterdown, south of Bristol city. The streets that he lived in throughout his time in Bristol were destroyed during the Blitz and subsequent post war redevelopment. The streets were completely renamed and there is now little to suggest what Bristol might have looked like during William’s time, except a number of churches, sometimes ruinous and a scattered collection of antique engravings.

Bristol St Mary Redcliffe parish, antique woodcut illustration

Not Many people could write in those days .so the person writing it wrote it the way he thought it would be.so mortimer became mortimore.same name/ same family. I am Diana allens 2nd cousin.sadly she died in Sept 2025.i miss her greatly.but she did leave all of this mortimer history for us to enjoy……mortimerwendy725@gmail.com

You refer to William and Jane Mortimer’s life in Bristol but following Jane’s death William is referred to as William Mortimore in his marriage to Mary Ann Tippins. Both were of course illiterate so was the change in spelling of the Mortimer/Mortimore surname down to the interpretation of the Vicar?