Founding father

The first known progenitor of the Devonshire Mortimers was John Mortimer, who was sworn to the office of tithingman in Stockleigh, the manor of West Budleigh, before September 1454, as recorded in the manor court roll of West Budleigh. Though this John is known only from a single document, we can infer much about him from surrounding sources. The place known as Stockleigh in the manor records was possibly either Stockleigh English, or Stockleigh Luccombe bear Upham, in the neighbouring parish of Cheriton Fitzpaine. A tithingman acted as the local leader of a tything, a small area of land and subdivision of a hundred. He collected the tithes, a tenth of income which was given to the church and paid in kind. As part of the responsibility, John Mortimer was to maintain law and order in the tything, which often involved reporting petty law breakers. The above entry in the West Budleigh manor court roll states that Mortimer brought to the manor court’s attention that “William Hurde tapped ale by false measures” and that “Hurde, Richard Paulyn, William Roser & Roger at Hole brewed ale & broke the assize.” The assizes were a law based on agreed commercial custom, and breaking it incurred a fine.

It is certainly fortunate that John was named in the document, as otherwise we may not know of him at all. To act as tithingman, John was presumably of standing in the parish and was perhaps a yeoman or small farmer. While obviously over the age of 21 at this point, John was presumably a mature man in his thirties at least, pointing to a birthdate in the early 1420s. As such he already had young sons who may have began the various branches of the family in Devon.

Whilst the parents of John Mortimer of Stockleigh can only be speculated, he was perhaps a son of John Mortimer of Wantage the juror who bore witness to various grants in Wantage between 1415-1447. John was presumably related to John Mortimer of Bromyard who lived in 1386. John, Robert, Thomas and Richard were all names favoured in the early generations of the family. Ancient English naming tradition dictated that men would name their first born son after their own father, even if it were the same. This was in order to honour their parentage. This naming system was most famously followed by the Mortimer family of Wigmore, who adhered to this naming system strictly, the main line never deviating from this dogma throughout the course of their existence. Whilst the medieval naming system declined over the centuries, by the 19th century becoming completely non existent, it is only reasonable to presume that the naming traditions had some bearing on the names fathers in the Mortimer family chose for their sons from the 15th century into the Tudor era. John was perhaps only distantly related to the Mortimers of Wigmore, Earls of March, who had such an important role in Medieval history.

15th century crisis

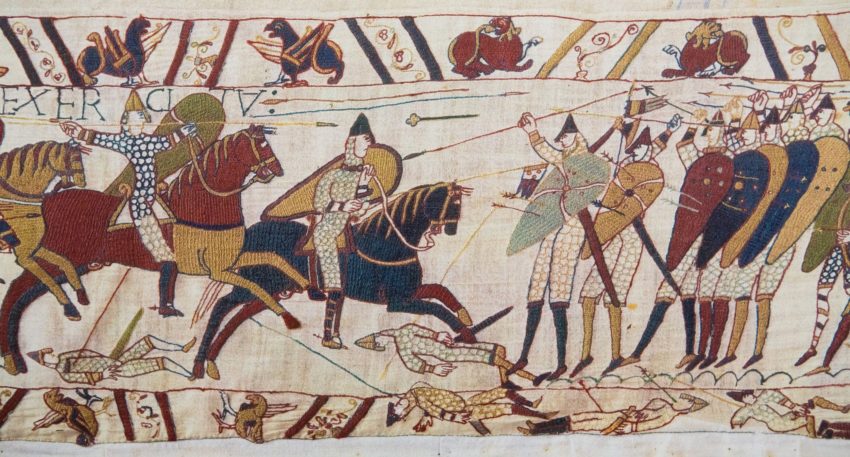

As a yeoman, John Mortimer was expected to bear arms when necessary, and he or his ancestors may well have participated in the various conflicts of the 15th century. The wars with France had come to an end in 1453 with French victory over the last remaining English forces at the battle of Castillon. Cannons were used to great effect in battle for the first time, and influence of the English on French soil was finally ended. By this time, the Mortimers had retreated from warfare and public roles, preferring to live peacefully on their estates. However, these were still dark and troubling times. The Hundred Years’ War with France had taken its toll, as French blockades reduced England’s exports. Meanwhile, multiple harvest failures and outbreaks of disease in livestock harmed nationwide agricultural production. England’s important wool trade was seriously reduced as cloth production fell, while cloth exports in the South West were particularly devastated. The impact of the great slump was felt particularly harshly among the poor, and many starved as a result. Merchants survived the disruption only by forming networks, enabling them to create a system of self protection. Taxes had been pushed exhorbitantly high by successive monarchs to fund foreign war, causing widespread dissent and rebellious feeling among the masses. Breakdown of the feudal system began to accelerate, as landlords were no longer able to guarantee protection or wages, meaning many servants became free from servitude but lost work. These factors combined with economic decline lead to the reduction of traditional power centres. In 1454, dangerous conflict was brewing. In Parliament, two factions emerged, one loyal to the ineffectual King Henry VI, and another which supported the Duke of York, Richard, a male line descendent of Edward III who had a strong claim to the throne through descent from the Mortimer family and Philippa Countess of Ulster. Tension eventually spilled over into armed conflict at St Albans in May 1455. The competing factions vying for control would become known as the Houses of Lancaster and York. The dynastic wars which they waged would tear the country apart and divide family loyalties across the entire establishment.

The crime of the century

These events may have felt distant to John but later that year, mid-Devon would feel the gathering storm. It was here in Cheriton Fitzpaine that one of the most notorious crimes in the Middle Ages was committed, that had profound ramifications both in Devon and nationally. One of John Mortimer’s neighbours was the esteemed lawyer Nicholas Radford, who resided in Upcott Barton, Cheriton Fitzpaine. Radford had twice served in Parliament, though having become frail with old age had by 1455 retired to his manor of Upcott. As Justice of the Peace, Radford had amassed a vast fortune, keeping £700 worth of plate and jewels at his town house in Exeter alone. This great wealth made Radford a figure of great respect but also a target in such a jealous society. In his legal work, Radford befriended Sir William Bonville of Shute, a fierce rival of Earl of Devon Thomas Courtenay. Though the Bonvilles had achieved greater social status to the Courtenay’s, they were from a lower background as barons. The Courtenay’s saw themselves as the premier county family and dispensers of county justice, looking down on the Bonvilles as upstarts. The two factions were often in dispute, with disagreements sometimes boiling over into armed conflict. Though Radford had served the Earl in his minority, his relationship with the Courtenays had long since deteriorated, leaving the Courtenay faction increasingly bitter and vengeful towards him. The simmering dynastic feud came to a head on the night of the 23 October, when the Earl’s son Sir Thomas Courtenay brought a group of 90 soldiers to Radford’s house and burnt down the gates. Accepting Courtenay’s word as a knight that he would not be harmed, Radford left the safety of his manor to treat with them. While away, a group of Courtenay’s soldiers ransacked Radford’s house, assaulting his servants and turning his poor wife out of bed, finally leaving with six of Radford’s horses laden with valuables. Satisfied with the theft, Courtenay bid his farewell to Radford but then directed his soldiers to kill him. One of his men ‘glayve smote’ the said Nicholas ‘a hidious dedlye stroke overthwarte the face and felled him to the grounde’, while another ‘yaf him a noder stroke upon his heade behinde that the brayne fell oute of heade’, leaving Radford’s body lying in the dirt. As if this was not enough, Thomas Courtenay’s brother Henry then seized the body and presided over an obnoxious inquest, absolving Thomas Courtenay of blame and directing Radford’s servants to bury him. When they reached the church, Courtenay’s men stripped his body naked and tossed it into the grave, before throwing the prepared tomb stones on top of Radford, completely crushing his body.

Radford’s respectable position as justice of the peace, combined with the devious nature of his killing, made his murder particularly notorious and shocking to even medieval sentiments. The incident was a direct affront to the rule of law, and showed the weakness of royal power in the provinces. Following the murder, open warfare was inevitable. Courtenay and Bonville clashed in battle at Clyst Heath near Exeter, in which Courtenay was victorious, who continued to pillage Bonville’s manor of Shute. The fallout contributed to the further development of the dynastic Wars of the Roses. Radford’s killers were never brought to justice, but Thomas Courtenay was executed following defeat at the battle of Towton six years later. John Mortimer would have witnessed these events from a close perspective as Radford’s neighbour, and may even have supported the side of the Bonvilles following such an affront to law and order. The West Country would be utterly devastated by war, and most members of the Courtenay family were either killed in battle or eventually executed.

It was into these tumultuous times that John Mortimer of Stockleigh’s eldest son, John, was born, around the early 1450s. Very little is known of his life. He lived through the Wars of the Roses, seeing Edward IV crowned after victory at Towton, and John would probably also have known that it was Mortimer ancestry that gave Edward his principal claim. Edward was usurped in 1470 after upsetting the Duke of Warwick, but regained power following decisive victory at the Battle of Tewkesbury. It was in the re-established reign of Edward IV that the first reference to John Mortimer the younger is found, and shows that conflict within the royal family was even reflected in conflict among the Mortimers of Devon. On 24 October 1477, it was alleged by the tithingman for Stockleigh English that John Mortimer attacked Robert Mortimer. Quite why John would turn against his own family member in this way remains a mystery. The two men were probably siblings, sons of the first John Mortimer, and their conflict may have revolved around an issue of inheritance. Despite their grievances, whatever they were, John and Robert presumably reconciled, as John named his son Robert after him around 1480. At the same time as the above feud, Thomas Mortimer was found to owe suit to the office of tithingman. Thomas appears to be the same generation as the above two, so was perhaps another brother. There might have been other brothers too, though their names do not appear in the above manor court roll.

The entire political landscape changed forever in 1485 with the fall of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth, an event that was a defining chapter at the close of medieval England. The House of Tudor was now established, which would see many changes take place to governance and the economy. In 1490, Robert Mortimer lived in Stockleigh English, and was sworn to office of tithingman, a role assumed by John Mortimer in 1495, perhaps Robert had either died or moved away by then.

West Country Turmoil

In 1496, Thomas Mortimer, perhaps the same Thomas as owed a debt in 1477, was declared an outlaw. Perhaps this outcome itself resulted from a debt action. An inquisition into his possessions was made by the sheriff, but little else is known about him.

On the other hand, the above Thomas may have participated in rebellion and been outlawed for treason. The new Tudor regime was unpopular in the more remote and conservative areas of England, and was subjected to numerous rebellions and uprisings, the most prominent of these being the Perkin Warbeck rebellion. Perkin Warbeck claimed to be Richard son of Edward IV, the younger of the Princes in the Tower, and contemporary sources claimed he did look much like the prince. The South West was particularly unruly, and many members of the yeomanry were angry with the high taxes of Henry VII. Scotland supported Warbeck’s faction against Henry VII, who decided to raise an army to invade Scotland. Parliament raised a forced loan to fund the army, which Cornwall contributed a disproportionately large share. Anger in Cornwall over the high cost of the tax, combined with the matter having little to do with them anyway, caused the Cornish to rise up in rebellion, joined by many of the leading gentry and yeomen of Cornwall. A large Cornish army began to march towards London unopposed, gathering support in the South West on the way. The Cornish demands were refused and the army defeated by a strong Royalist force at Blackheath. The recriminations on Cornwall would be severe, leading to another uprising only a couple of years later.

Family groups

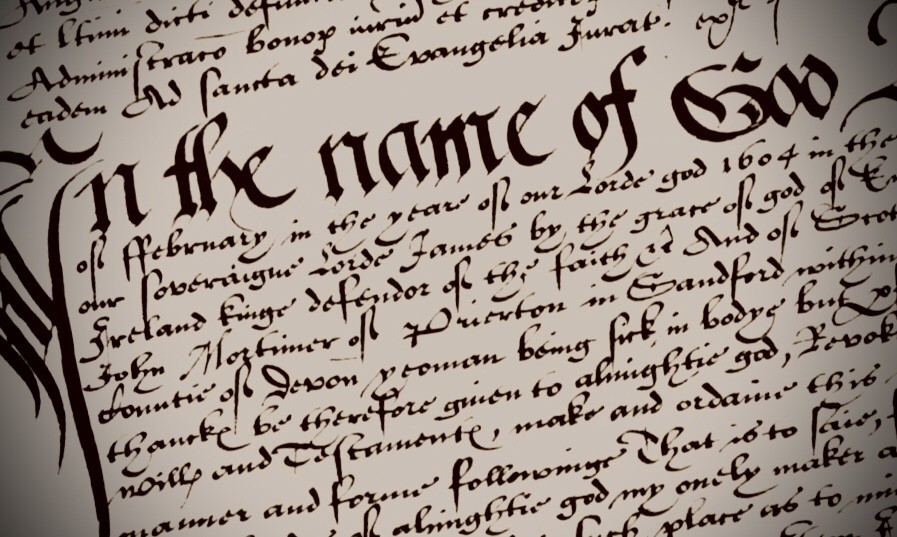

Around the turn of the 15th century, John Mortimer, who seems to have enjoyed estates at both Woolfardisworthy and Stockleigh, married his son Robert to Joan, the daughter of Henry Sharland of Morchard Bishop, a wealthy yeoman. John agreed to bestow land on Joan as part of the marriage settlement, but by 1503 had failed to fulfill his promise, causing Sharland to sue John in the Court of Chancery. John’s son Robert died before 1524, when the first tax subsidy was enacted. John still lived in Emlett, Woolfardisworthy, with an income of £14. Robert’s widow, Joan, held land in either Sandford or Stockleigh English. Following these events, other Mortimer families sprang up in Devon that may have been related to the earlier Mortimers of Stockleigh. These included the branches in Sandford, Tedburn St Mary, Bradninch, Totnes and Stokenham.

Explore related Mortimer families

Recent Comments