A closer look at place names

Every town or village in the UK has its own story to tell. Often just looking at a place name can reveal a snippet of interesting information about a location.

The British Isles has a collective heritage from thousands of years of settlement and invasion by various peoples. The first to pass their unique heritage to place names were the native Britons, or Celts, who originally came from Central Europe and were a part of a much wider movement of European peoples and sharing of culture during the Iron Age.

A quick background

The Celts settled all corners of the British Isles, and eventually divided into three groups, the Irish, the Picts in what is now Scotland, and the Britons who inhabited the regions of modern England and Wales.

Next came the Romans, who eventually conquered the lands of the Britons, but eventually merged with the native population, creating what is now seen as a distinct Romano-British culture. Hadrians Wall separated the Roman province of Brittania and Caledonia, which continued to be ruled by the Picts. The Romans called the island of Ireland Hibernia.

When the Romans abandoned Britain in 410 AD, huge changes were afoot. At the same time as the Barbarian invasions which ripped the Western Roman Empire apart, Britain witnessed wide scale migrations and civil strife, in an era now termed the Dark Ages, due to the lack of written records.

A tribe from what is now Cumbria in England moved South West and became the Welsh, while a tribe from Northern Ireland known as the Scots conquered the Picts and gave their name to Scotland.

Beginning in the mid 5th century, the Brits were terrorised by invading Germanic hordes from Northern Continental Europe- the Saxons, Angles and Jutes. The Saxons were most numerous but it was the Angles who gave their name to what is now England.

The Saxons converted to Christianity in the 7th century, and established the Anglo Saxon Heptarchy, a realm of seven different petty kingdoms which governed England.

However, the British Isles had not suffered the last of foreign invasions. The fearsome pagan Vikings marked their arrival in England by attacking the monastery at Lindisfarne, Northumbria, in 793 in a notorious raid now subject to legend. The Vikings made an indelible mark on the whole of Britain, and many other parts of Europe, which has stood the test of time.

This distinctive heritage from so many different cultures is what gives Britain its collective identity. Throughout the UK, place names can be observed which bear witness to the tumultuous events of Britain’s past. Here is a description of the different roots of British place names, by language or culture, that should help to discover what the origin is for the vast majority of British place names.

How places were named

Before the development of settlements, the early inhabitants of Britain simply gave names to noteworthy natural features, such as hills, valleys, mountains rivers, islands and shorelines. Original settlements were built in important strategic or trading locations, like on a river, the mouth of a river, a confluence, or on a hill or ridge overlooking surroundings. The development of a place name often combined names for multiple features, such as the mouth of a certain river.

The Britons

In ancient times the Britons inhabited the southern half of the island of Great Britain, what is now England and Wales. The Britons spoke the Common Brittonic language, which is represented today by Welsh, Cornish- a virtually extinct local language, and Breton, which is spoken in a very small part of Brittany, France. Brittonic place names reflect the ancient British landscape. The Britons had many different words for geographic features, including the hills, streams, valleys and woods which characterised the landscape.

The Brittonic word for hill was ‘bre’, in Welsh is ‘bryn’, while the summit of a hill was the ‘ben’. Areas of upland were called ‘blen’. The Welsh for slope is ‘rhiw’. A valley was ‘cwm’. A more narrow river valley might have been called ‘glen’. The word ‘pen’ designated the headlands. Rivers were called ‘afon’, like the river Avon. The source of the water was called ‘blaen’ while the mouth of a river was the ‘aber’. A crossing or ford of the river would have been called ‘rhyd’. The Brittonic word for lake was ‘pol’, and an island was ‘ynys’. Britain had retained many of its ancient forests, which woods were called ‘coed’. A thicketed area was ‘cadgwith’. Descriptive terms applied to landscape features included ‘mawr’ for large, and ‘cul’ for narrow.

After Roman colonisation, the Christian Romano-Britons built settlements and churches, but were pushed back by the Saxons into the fringes of Britain, Wales and Cornwall. Here their words for built features gave rise to many place names recognised today. Perhaps the most important of these was ‘llan’, meaning parish, a small area centred around a church, which would have been the beating heart of any community. Villages were named after the patron saint of the parish church. Llan is probably related to the word for a group or community, reflected in the Scots-Gaelic word ‘clan’.

The Britons’ word for the church itself was ‘eglwys’ while a town was ‘din’ or ‘tre’. A monastery was ‘kil’. A port was called ‘porth’ – indeed one of the English words which comes from Brittonic. Areas were often contested between the Welsh and Saxons, or between different Welsh tribes. In these areas, the Welsh built forts ‘dinas’ and military camps ‘caer’.

Irish and Scots

In Ireland, people spoke the ancient Gaelic language, which shared a root with Bretonic. The Irish Dal Riada tribe spoke Gaelic and conquered the Picts north of Hadrian’s Wall. These people were the Scots, who settled the country we now know as Scotland. Thus Scottish place names bear a certain resemblance to places in Ireland.

In Old Irish, the words for hill or upland areas were ‘ard’ or ‘auchter’, while ‘ben’ meant summit. ‘Crag’ and ‘drum’ meant the crags and ridges, so symbolic of the Scottish highlands. A rocky hill was ‘knock’ similar to the Bretonic word ‘cwnyc’. The Old Gaelic for valley was ‘glen’, while ‘strath’ signified a wider valley.

The Scots Irish shared the Gaelic word ‘avon’ for river with the Britons. Where a river reached the sea was called ‘inver’. The Gaelic word for a lake or inlet was ‘loch’, one of the few Gaelic words still in widespread use outside the language. Gaelic descriptive terms included ‘more’, for large and ‘kyl’ for narrow.

The Irish and Scots built churches and farms and these are a significant source of place names. Many of these words sound similar to Bretonic. The Gaelic for church was ‘eglais’, and a monastery was ‘kil’. The Gaelic word ‘balla’ meant a farm or homestead. ‘Auch’ was the word for a field while a an enclosed field was a ‘gart’.

Anglo Saxon

The Anglo Saxons came from what is now Northern Germany, in the region bordering Denmark. The word English comes from the Angles, who invaded the Southern part of Britain with the Saxons. The Anglo Saxons spoke Old English, a West Germanic language, it’s oldest literary attestation is in the 7th century. The Anglo Saxons eventually conquered all of what is now England and divided into 7 independent kingdoms. As a result, the vast majority of English place names have an Anglo-Saxon origin. The early Anglo Saxons belonged to many distinct tribes who settled in different areas and owned their allegiance to different rulers. They were Christianised in the 7th century following the Gregorian Mission of 597. The Old English for tribe was ‘ing’. Settlements such as Reading and Hastings are named after the Readingas and Hestingas tribes.

Many Old English words can be understood today. A hill was a ‘dean’ while a valleys was called ‘dale’ or ‘vale’. The Bretonic word cwm for a small valley was adopted into English as ‘combe’ and described a small valley without a stream. ‘Hope’ meant an enclosed valley. The Old English for rocky or stony was ‘stan’.

In Old English a river was called ‘ax’, which can be observed with several rivers today, notably the Exe and Ax rivers in Devon. A ‘beck’ meant a small stream, while a large stream was termed ‘bourne’. A river was crossed at the ‘ford’. Many towns developed where rivers met the sea at their ‘mouth’, such as Exmouth, or Tynemouth. A lake was called ‘mere’ such as Windermere and an island ‘ey’. The word for a swamp was ‘moss’.

The Saxons had lots of words for wooded areas. The word ‘wood’ features in many place names. A ‘shaw’ meant thicket. The woodland edge was called ‘firth’ and a wooded hill ‘hurst’. In Old English, ‘wold’ or ‘weald’ denoted an elevated area of high woodland. The words for specific trees sometimes feature in place names, such as with ‘ash’, or ‘ack’ for oak, which bears similarity to the word acorn.

The origin of the word home is in ‘ham’ which was short for ‘hampstead’ or homestead. Likewise ‘stead’ meant a home. A ‘cot’ meant a cottage. The Saxons often guarded their settlements. An enclosed home was called ‘worthig’ meaning warded place, which was shortened to ‘worth’. Likewise ‘haeg’, shortened to ‘ey’ meant enclosure. The word ‘hay’ destined places enclosed by a hedge.

The word town comes from the Saxon word ‘ton’ for settlement. A ‘stoke’ was a little settlement or village, dependant on a nearby town. A ‘bury’ or ‘borough’ was a fortified town, originating from the old German word ‘burg’ meaning fortified. Most German towns built up around a castle end in this word. In Old English, the word for market was ‘chip’, such as London’s Eastcheap. On the coast, ‘pool’ meant a natural harbour, while a constructed wharf was called ‘hithe’. The Saxon word ‘port’ continues in unaltered form. After the Saxon settlement some Roman military forts, ‘castrums’, continued in use. In Old English, the Roman castrum was corrupted to become ‘cester’, forming a component of the many English towns with a Roman heritage, such as Gloucester and Chichester. Another English corruption of Latin was ‘wick’ from the Latin ‘vicus’ meaning trading place. Other influences of Latin on English place names include ‘street’, and the words for ‘magna’ large, and ‘parva’ small.

Though the Saxons invaded and attacked the Brits, they were also well known for their farming skills. Many Saxon place names derive from farms or fields. The Saxons settled areas and intermarried with local populations, also taking on some Bretonic words. A ‘leah’ meant a woodland area cleared for farming. ‘Farm’ and ‘field’ feature in many place names. The word ‘mead’ evolved into the word meadow. The Saxons also kept ‘shep’ sheep, ‘swine’ pigs and ‘kine’ cows, which give place names a pastoral connection.

After the conversion of the Saxons to Christianity, religion continued to play an important role in daily life. The church was a centre of the community. Important monasteries were called ‘minster’, while ‘stow’ described a holy location or place of pilgrimage.

The words for multiple features of a place were often rolled into one. The most common elements of place names was the name for specific rivers and farms. A further way of differentiating places was by designating their direction. The words for directions were ‘nor’ North, ‘ast’ East, ‘sud’ South, and ‘wes’ West. Examples include Northleigh and Southleigh in Devon. Most English place names developed by the 9th century, and words changed as the language evolved into Middle English, with more modern words like ‘market’ being added to places.

The Vikings began raiding the British Isles in the 8th century and were often in conflict with the Saxons. As well as ruling large parts of Scotland, the Vikings settled the East and North of England and ruled over an area known as the ‘Danelaw’, influencing place names in these areas. The Vikings spoke Old Norse which as a Germanic language had some similarities to Anglo Saxon (Old English). The Norse element in place names reflect the landscape features most important to the Vikings. In Old Norse the word for clearing was ‘thwait’ while ‘Howe’ meant a mound. Ridges were called ‘rigg’ and ravines ‘gill’. The word for inlet was ‘firth’, and ‘wick’ meant a bay. Waterfalls were called ‘foss’ while ‘keld’ meant a natural spring. In Old Norse, a ‘bost’ meant farm while a ‘toft’ was equivalent to a homestead. The Norse word ‘tun’ for town was similar to the Saxon ‘ton’. A village was called ‘by’, such as Whitby, and the Norse for road was ‘gate’. A church was called ‘kirk’.

What is the word origin of the town where you live? Post in the comments below!

Further reading:

Go a step further. Discover your surname origin!

Other recent posts:

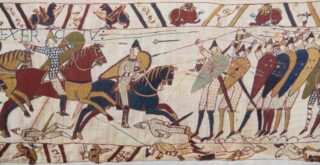

An arrow in the dark. The story of Harold Godwinson, England’s last Saxon king, and the Battle of Hastings 1066

The Mortimers of Coedmore, Cardiganshire. An existing Mortimer family that can be traced back to Medieval times!

Recent Comments