Men of the Marshes

The Mortimer surname’s origins date back a thousand years to eleventh century Normandy. By this time, the village of Mortemer-sur-Eaulne had developed in the Pays de Bray region of Normandy, between the historic cities of Rouen and Amiens. The old French word ‘bray’ meant a swamp or marsh, while the place name Mortemer also derived from such a description. The Latin word ‘mort’, meaning die, combined with the old French ‘mer’, for lake or sea, can be translated as ‘dead water’ a poetic description of the stagnant water of the Pay de Bray’s marshland. Mortemer castle was constructed in 1020, and by 1054 had come in to the hands of Roger FitzRalph, a Norman knight. Fitz meant son, and as a son of Ralph de Warenne, Roger was distantly related to William Duke of Normandy. His mother Béatrice de Vascoueil was apparently a niece of the duke’s paternal grandmother Duchess Gunnor.

The Normans were originally the “Northmen” from Scandinavia, descended from the Vikings who raided Europe in the eight to tenth centuries. A powerful Viking chieftain named Rollo conducted raids along the French coast. In one such raid he kidnapped a young Brittonic noblewoman Poppa of Bayeux, and married her in the Viking fashion. He eventually returned to the region to settle permanently, establishing a separate County in northern France. Rollo founded the line of Dukes of Normandy, and is an ancestor to all subsequent royal houses. The Normans soon converted to Christianity and adopted Frankish customs, making an indelible mark on the region. They transformed Normandy by building magnificent churches, abbeys and castles, one of which was the castle of Mortemer. The medieval Mortimers were ultimately descended from Vikings and seemingly inherited their warlike nature.

The Battle of Mortemer

The French King Henry launched an invasion of Normandy in 1054, supported by his brother Odo. Targeting the Norman county of Évreux, Odo invaded Eastern Normandy supported by the French Counts Renaud of Clermont and Guy of Ponthieu. Together they pillaged the countryside and caused widespread devastation. Whilst Duke William intended to lead the defence of Normandy against Henry, he sent an allied army to relieve Évreux, lead by Robert of Eu, and supported by Roger FitzRalph and Walter Giffard.

The French forces were more numerous than the Normans, but through their pillaging they had become scattered and disorganised. Encamping at Mortemer Castle, they soon descended into drunken debauchery. Sensing opportunity, Roger FitzRalph used his superior knowledge of the terrain to launch a surprise attack. Making a move before dawn break, Roger’s army ambushed the French, inflicting heavy casualties. In a fierce battle that lasted several hours, the Normans ultimately succeeded in gaining ground and routing the invaders.

Weighed down by heavy chain mail, many French soldiers drowned in the boggy conditions, while those soldiers who stayed on the battlefield were either killed or captured. The French commander Guy of Ponthieu surrendered and Roger FitzRalph personally captured Ralph de Montdidier, Count of Valois. The Norman victory was clear and decisive. Upon hearing word of the defeat, King Henry decided to retreat without engaging the Duke’s forces on the other side of the Seine.

This was an important victory for Duke William, as it secured Norman territory and promised stability of his Duchy. Guy of Ponthieu was imprisoned for two years and forced to pay homage, while Ralph of Valois was made a captive of Roger. However, as Roger’s feudal overlord and father in law, Roger treated him fairly. He accommodated the count at his castle and afterwards released him, incurring the wrath of Duke William.

For releasing the Duke’s enemy, Roger was punished with banishment. His estates in Normandy were confiscated, and Mortemer was given instead to Roger’s young kinsman William de Warenne, who had conducted himself admirably in the battle. Thus Mortemer was lost, and would never be within the family again. Despite this setback, Roger remained proud of his role in defending Mortemer from Normandy’s enemies, and took the name of the castle despite losing the lordship. He was known as Roger de Mortimer, essentially Roger ’of Battle of Mortimer fame’. The fact he didn’t use the name while lord there, but instead some time after, shows that the Mortimer surname is perhaps derived from the battle rather than the lordship itself.

The Conquest of England

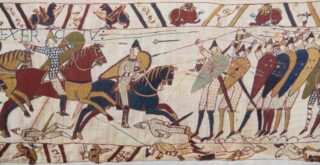

Around the time of the battle, Roger’s son was born. He was named Ralph after his paternal grandfather, a Norman naming convention that the family would follow for centuries. Roger Mortemer was forgiven for his actions and granted the town of St Victor-en-Caux, Normandy, 25 miles West of Mortemer-en-Bray. By the time of the Norman invasion of England in 1066, Roger was by then in his 40s, with significant military experience. He had already shown his skill in battle and may well have been among the knights who sailed with William to England and fought in the Battle of Hastings. At the time, Ralph was likely a young squire and might have participated, but he was probably too young to fight. The twelfth century chronicler Wace writing a hundred years later, describes a Hugh Mortimer fighting at Hastings, but this must be in error as no such Hugh is known from contemporary sources. Only the names of fifteen men are confirmed by contemporary sources to have accompanied William in the conquest, including bishop Odo of Bayeux and Eustace of Boulogne, who both feature in the Bayeux Tapestry. Many more knights participated, and those who were granted land after the conquest were presumably so rewarded for their military service to the new King.

The Norman conquest changed England forever, transferring the feudal way of life from France. The surviving Saxon leadership in the country was immediately excluded from all office or property, while areas which resisted such as Yorkshire and the North were burned to the ground. English land was partitioned among the invaders on a scale seen neither before nor since. William the Conqueror as monarch took ownership of all English land, a legal status quo which technically continues to this day. The king divided the spoils of conquest among his lords and knights who had been loyal and supported him throughout the hard times. Twenty years after conquest, the new political landscape was reflected in Domesday. This ambitious national land survey was undertaken with the purpose of assessing the full wealth and resources of the country, and showed who retained property in every parish of England.

Though Roger Mortimer was granted land in England, he remained more interested in his Norman lands than the realm across the channel. Roger stayed in Normandy in the 1070s, and evidently spent his final years focused on religious devotion. He might not have visited England at all. In 1074 he petitioned for the Priory of St Victor to become an abbey, and he evidently died sometime after this date, upon which he was succeeded in his estates by his son Ralph. Ralph de Mortimer expanded the family’s horizons and was the first to spend a significant proportion of time in England. Ralph engaged in the Norman conquests of southern Wales and played an important role in the development of the Welsh Marches, the tumultuous border between Wales and England. With Ralph’s marriages and sons, the family line would become secure and expand into several offshoot branches by the 12th century. The Mortimers were certainly in England to stay.

Continue to Chapter 2. The Welsh Marches – Life on the frontier of England and Wales

Recent Comments