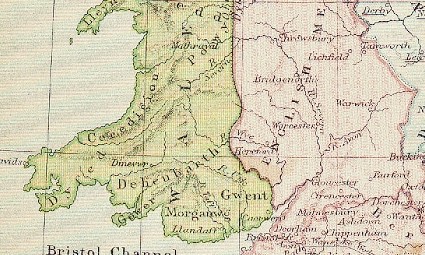

Origin of the March

The ancient word for boundary, the March marked a borderland between two competing centres of power. In modern English, original meaning of March is reflected in the word margin. The Welsh Marches were the loosely defined lands on the margins of England and Wales, which throughout the Middle Ages were dominated by the power of the Marcher barons. The Marcher lordships had a unique status. The lords who controlled the March had great wealth and power, and exercised considerable independent authority, away from the prying eyes of the King. Whilst England existed as a united realm, Wales remained a collection of separate principalities, sometimes in conflict but united by shared ties of language and culture.

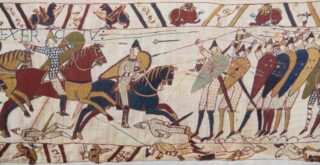

Immediately after the conquest, king William I looked towards England’s borders. Eager to counteract the threat of the Welsh across the border, he installed three of his most trusted followers as Earls in the Welsh Marches. William FitzOsbern, Hugh de Montgomery and Hugh d’Avranches were appointed the Earls of Hereford, Shropshire and Chester respectively. They were invested with significant power and tasked with pacifying the turbulent Welsh, by any means necessary.

Fortification of the Marches

The Normans brought their own advanced skills in castle building to England and the Welsh Marches. Castles would prove increasingly important in the centuries ahead, providing the key to securing an effective hold on a region. The first castles to be built in the Welsh Marches were small motte and bailey castles, much like Mortemer castle in Normandy. Over time, fortifications improved as castles were rebuilt in stone, with extended battlements, towers and curtain walls.

In reality, the Marcher lords ruled their estates like kings in their own right, raising taxes, levying armies, and every so often, invading their neighbours. Constantly restless, they were always looking for ways to gain more wealth and expand their territory. This made Wales a target, and Welsh lands became a battleground for aspiring Norman knights.

The Conquest of Maelienydd

One such knight was young Ralph Mortimer, who arrived in the Welsh Marches not long after the conquest. Imbued with a youthful vigour and determination, Ralph led the conquest of the Welsh region between the Wye and Severn rivers, known as Maelienydd or Ferlix. From the 1070s, Ralph consolidated his power by building castles at Dinieithon and Cymaron, using the latest Norman building methods.

For his achievements, Ralph was rewarded with extensive lands by the King, but this was not the limit of his ambition. When FitzOsbern’s son Roger Earl of Hereford rebelled, Ralph seized an opportunity. He assisted the king by attacking the Earl’s castles, helping to bring an end to the rebellion. Ralph acquired FitzOsbern’s castle of Wigmore, which would become the family’s principal seat of power for generations.

Inheritance

Around 1080, Ralph’s father Roger died and Ralph inherited all his estates in both Normandy and England. He married first Millicent (d. before 1088), by whom he had a daughter Hawise, and secondly Mabel, in about 1090. Mabel bore him four sons, Roger, Hugh, William and Robert. Ralph’s daughter Hawise married Stephen Count of Aumale, son of William the Conqueror’s sister Adelaide. Ralph continued to faithfully serve King William, and gained over 200 manors for his loyalty. Though he did not have time to visit them all, the income from these estates would prove especially useful in funding Ralph’s military exploits.

Leadership Crisis

When William the Conqueror died in 1087, his third son William Rufus was crowned while his eldest son Robert Curthose became Duke of Normandy. Loyalties were divided between the two rulers, creating a dilemma for barons with land both sides of the channel. For aggrieved lords, the solution was simple, to unite the Norman realms under a single ruler. The barons preferred Curthose for his weaker authority, so in 1088 rebelled against Rufus with the aim of replacing him with Curthose. The rebels were lead by King William’s uncles, the Conqueror’s half brothers Odo bishop of Bayeux and Robert Count of Mortain, two of the most powerful figures in Norman politics.

Ralph Mortimer participated in the rebellion of 1088, joining with other rebels in laying waste to the King’s manors or those of his loyalists. William II defeated the rebellion through a combination of direct action and appeasement. Offering land and money to pacify the barons, he laid siege to the stubborn rebels’ castles, capturing their leaders. For his involvement, Ralph Mortimer was banished, and Wigmore confiscated. Returning to Normandy, Mortimer continued to undermine the King by supporting Curthose, acting as witness to his various religious charters.

Continuing grievances among the barons saw them once again rise in rebellion in the 1090s. Stephen Count of Aumale emerged as a popular figure among the rebels, and a conspiracy was formed to replace Rufus with Stephen. Ralph Mortimer conspired to assist his son in law in his quest for the throne, but William Rufus again defeated the rebellion through a combination of military action and diplomacy.

In 1096, Robert Curthose joined the First Crusade for Jerusalem, departing Normandy for the Holy Land with Stephen of Aumale and many other knights. Rufus subsequently died in a suspicious hunting accident in the New Forest, and his younger brother Henry had himself crowned before Rufus was even laid to rest. In Duke Robert’s absence, Ralph pledged allegiance to the new king Henry, who restored the Mortimer estates. Returning into royal favour, Ralph was appointed Lieutenant of Normandy and supported Henry’s invasion of Normandy in 1104. The fighting came to a conclusion at Tenchebrai in 1106, where Henry was victorious in a decisive engagement. Curthose was imprisoned, and spent the rest of his life in captivity. Since the duke had been a thorn in the side of the king for years, his defeat ushered in a period of stability under King Henry.

Succession

After Tenchebrai he retired from martial duties to focus on his spiritual obligations, for though he lived by the sword he above all wanted to secure access to heaven. He firstly founded a college of priests at Wigmore in 1100, which laid the foundations for a religious house there. In old age, Ralph also made a gift to Worcester Cathedral Priory, with the assent of his sons. He died sometime after 1115, when the Lindsey Survey of Lincolnshire was compiled. Ralph’s legacy was assured in the succession of his sons, between whom he divided his lands.

Anarchy and disorder

After coming of age, Ralph’s eldest son Roger Mortimer was knighted, perhaps by Stephen Count of Boulogne, grandson of William the Conqueror. Roger supported Stephen in his claim to the English crown, and perhaps became one of Stephen’s personal retainers. Though Stephen was well liked by the barons for his temperate personality, his claim was contested by Henry’s daughter Matilda. Following the death of King Henry in 1135, Roger Mortimer joined Stephen in his invasion of England. During the resulting civil war, Roger became a trusted military adviser to Stephen and commanded a royal army against rebels near Bristol in 1137. However Roger died soon after, perhaps in battle. With no lawful issue, he was succeeded by his brother Hugh, who took possession of the vast Mortimer estates.

Hugh had grown up in Normandy, inheriting over thirteen knight’s fees. He supported King Stephen and may have been one of his retinue. Upon coming to England, he commemorated his brother Roger in a grant to Kington St Michael nunnery, which preserved the memory of both his brother Roger and father Ralph. Hugh continued the work of his father by founding Wigmore Abbey in 1142. Though already in his fourties, Hugh saw the need to take a wife and married the widow Maud de Belmeis, widow of Philip. They had four sons; Ralph, Hugh, Roger and William.

Advance into Wales

Hugh made Wigmore Castle his home, refortifying the walls and enhancing the living quarters. Aiming to recover the lost Norman estates in Wales, Hugh invaded Maelienydd in 1142, advancing into Welsh land with considerable success. Madog ab Idnerth’s sons Hywel and Cadwgan were killed in battle, and Hugh captured Cymaron castle, repairing the outpost as a base for further invasions. In 1146, Hugh invaded southern Maelienydd, causing the death of Maredudd ap Madog.

Resistance to Henry II

Hugh remained a loyal supporter of King Stephen throughout the lawless period of Anarchy, which lasted for nearly twenty years. Empress Matilda eventually abdicated her claim in favour of her son Henry, who succeeded to the throne in 1153. Soon after his succession, Henry built up his power base and demanded the return of royal castles. Hugh de Mortimer resisted, and seized control of Bridgnorth. When Henry besieged Wigmore, Hugh was forced to surrender, but his lands were eventually returned. Hugh remained stubbornly resistant to the new king’s authority, and in 1155 once again refused to submit. Henry responded by laying siege to Hugh’s castles, razing Cleobury to the ground. Upon Henry’s siege of Wigmore and Bridgnorth, Hugh finally submitted to royal authority. At the Council of Bridgnorth, he agreed to return Bridgnorth to the crown in return for holding Wigmore.

Hugh lived into old age and died in 1185, when he was succeeded by his third son Roger, born c.1153. Roger was perhaps the first Mortimer Lord of Wigmore to be born outside Normandy, and continued to press invasions in the Welsh Marches.

Continue to Chapter 3. The Struggle for Welsh Power – Dynastic conflict in the Welsh Marches and the struggle to control Wales.

Recent Comments