The fight to survive

The Middle Ages were a dangerous time. Even if unharmed by war, plague, corruption and famine, people still faced the daily hardships of medieval life. For the ruling class, survival was not much easier. Nobles faced the perils of battle as an occupational hazard, while aspiring knights competed in dangerous medieval tournaments. With lethal weapons and few precautions, mortal injury in tournament was a frequent danger, with many knights dying of accidental falls and wounds.

Such was the fate of young Hugh de Mortimer, son and heir of Hugh, Lord of Wigmore, who was killed in a tournament at Worcester shortly after 1175. Hugh’s older brother, Ralph had also predeceased their father, perhaps also falling victim in a tournament. Though Hugh was married to Felicia de St Sidon, he left no children. It was up to his younger brother Roger to assume the lordship, and step up to the challenge of running a medieval estate while navigating the dangerous politics of medieval England. This Roger would have to learn the hard way.

Battles in Wales

Roger first gained military experience by serving King Henry in the conflict with his son Henry the Young King in 1174. Inspired by his father’s victories in Wales, he invaded Maelienydd without royal consent in 1179, violating a treaty. Roger killed the Welsh ruler of Maelienydd Cadwallon ap Madog in battle, which unsanctioned attack infuriated King Henry. Roger was imprisoned at Winchester, and held there for nearly three years.

To Roger’s fortune, he was well looked after in his confinement, and upon his release returned to Wigmore and succeeded his father before 1185. He married Isabel daughter of Walkelin de Ferrers and they had three sons Hugh, Ralph and Philip. The warlike King Richard followed an aggressive policy against the Welsh, so in 1195 following a Welsh attack, Roger joined forces with Hugh de Say to lead a royal army into Maelienydd. The marcher lords perhaps underestimated the strength of the Welsh, who surprised the invaders at New Radnor. Here in 1196, the Lord Rhys attacked and burned Radnor castle which was owned by William de Braose, and then set forth to confront the Normans. Roger Mortimer and Hugh de Say assembled a large army in the valley “with the greatest splendour” but they were promptly ambushed by the Welsh who were presumably concealed in Radnor forest. The lord Rhys “burst upon them” “in the manner of a lion” and “immediately turned them about in flight”. So it was the Welsh won a great victory, killing forty knights and many soldiers. Roger’s compatriot Hugh de Say was also killed in the fighting. This was a terrible set back for Roger, but he was able to regroup and recover his position, eventually subduing the province by 1200. Radnor would continue to be a constant point of contention between the Welsh and Anglo Norman marcher lords. Over the next century it changed hands numerous times.

Like his forebears, Roger retired from battle in later life to focus on his religious obligations, issuing a charter of rights to Cwmhir Abbey, a Cistercian monastery which supported 60 monks at its height. Wigmore Abbey also continued to grow since its foundation stone in 1172. In 1183 he made a charter to an abbey in Normandy, describing his grandfather Ralph de Mortimer and many other relations.

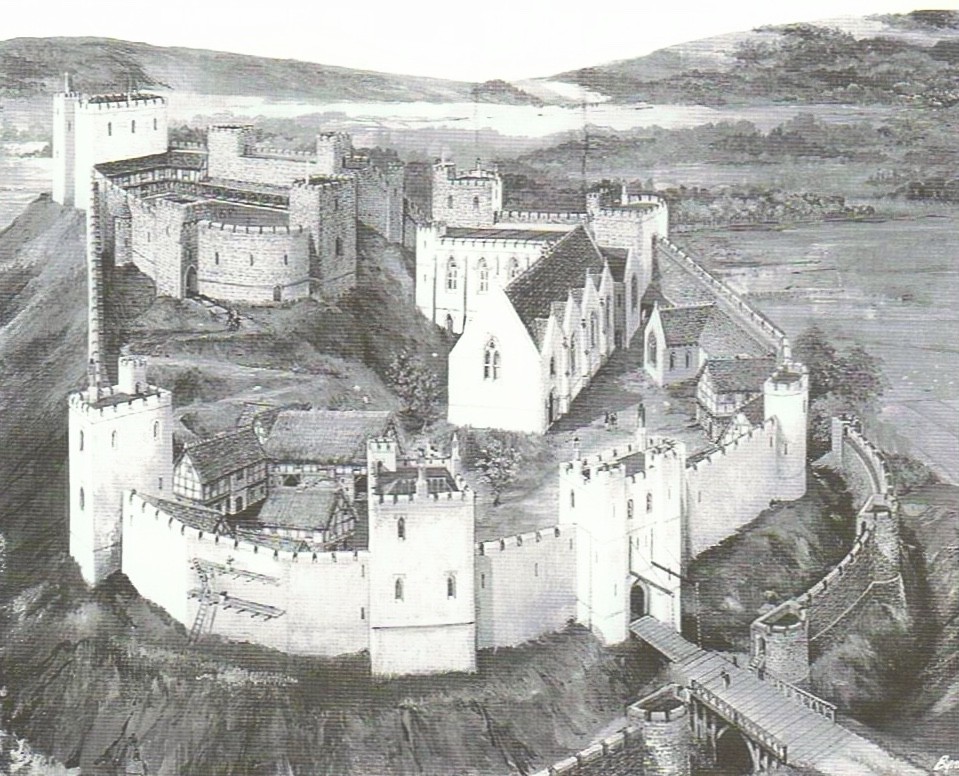

The Mortimer power base

From their home at Wigmore Castle, the Mortimers used the art of diplomacy to further their own political agenda. The marriage alliances pursued by the family reflected their political ambitions and enhanced their influence in the Marches. In the late 12th century, Roger Mortimer negotiated a marriage between his son Hugh and Eleanor, daughter of the infamous Baron William de Braose.

As Lord of Bramber, Braose was arguably the most powerful Marcher Baron and a favourite of King John. Out of all the Marcher Lords, Braose held a particularly brutal reputation. In the Christmas of 1175 he invited three Welsh princes to feast at Abergavenny Castle, but then murdered them in the Great Hall, apparently in vengeance for the death of his uncle. The event became infamously known as the Abergavenny Massacre. This grievous action drove an irreparable wedge in Anglo-Welsh generations, as the Braose name became a byword for dishonourable dealing and Braose descendants faced universal hatred. Lord Braose fell spectacularly following a quarrel with King John in 1209, who captured his wife and son and starved them to death. Braose a pauper in exile, perhaps just vengeance for an unpunished tyrant. His family’s mistreatment was though remembered by the barons who drafted Magna Carta in 1215, which brought forward the law that no man should be unlawfully imprisoned or condemned without trial.

A royal connection

Roger Mortimer died in 1214, and was succeeded by his son Hugh. It was the terrible misfortune of Hugh to die in tournament in 1227, much like his uncle and namesake. He had no surviving children and Eleanor his widow withdrew to become a nun at Iffley. Hugh’s brother Ralph succeeded to the Lordship, after previously having served in the household of the great knight Sir William Marshal. Such a connection could only have benefited Ralph when it came to arranging marriage. Hugh Mortimer’s brother Reginald de Braose’s widow was the Welsh princess Gladys Ddu, or “the Dark Eyed” from the house of Gwynedd, whose step son William had also married Eva the daughter of William Marshal. Ralph Mortimer and Gladys were wed soon after Ralph assumed the lordship, presumably concluding an agreement between the marcher lords and Gwynedd. Famed for her beauty, Gladys was the daughter of Llewelyn Prince of Gwynedd “the Great” and his wife Joan, illegitimate daughter of King John, whom Llewelyn married in 1205 on the condition that only their lawful issue would inherit the Welsh throne. Llewelyn effectively disinherited his eldest son, which continued to have political ramifications in Wales.

Marrying Gladys was quite the political achievement for Ralph, and also brought him closer to the young King Henry III, who was Gladys’ uncle. Being brought up in a royal family, Gladys would have learned both Welsh and French and been educated. She brought Welsh ancestry into the Mortimer family, connecting succeeding generations with the old Welsh princely houses. Together Ralph and Gladys had three sons; Roger, Hugh and Peter.

Relationship with the Braose family

Gladys was born c.1207 and betrothed at a very young age to Reginald de Braose as his second wife. Young enough to be his daughter, the marriage was highly political and likely never consummated. Her step son William de Braose began an adulterous affair with her mother Lady Joan of Wales, wife of Llewelyn. During marriage negotiations between Prince Dafydd, and William de Braose’s daughter Isabel, William was caught in Lady Joan’s bedchamber. He was subsequently captured, brought back to Wales, and publicly executed, though the marriage between his daughter Isabella and Dafydd ap Llewelyn subsequently went ahead regardless. This certainly would have been a strange wedding ceremony, following as it did from the bride’s fathers death at the order of the groom’s father.

Fortifying the Marches

Above all, the Mortimers coveted Wales and devised to expand their Welsh territories. Ralph claimed Knighton from Llewelyn of Gwynedd, who died in 1240. Eager to retain control of the borders, Ralph Mortimer began a campaign of castle building in Maelienydd, erecting castles at Knucklas in the 1220s, and at Cefnllys in 1242. Both were motte and bailey castles atop natural hills, designed to defend existing villages in Maelienydd from border raids. Ralph was known as a warlike figure and vigorously defended Mortimer lands from invasions.

Succession

Ralph died in 1246 and was succeeded by his eldest son Roger, who was born c.1231. Through his maternal grandmother, Roger was descended from King John. At an early age, he was married to Maud, a daughter of William de Braose and Eva daughter of William le Marshal. As a squire in the Welsh Marches during the mid 13th century, Roger was exposed to battle from a young age, giving him vital experience in the field of combat. He also witnessed castle construction first hand. King Henry took Maelienydd into his possession in 1246, but Roger persuaded him to give it back. In 1247 he took full possession of his inheritance, despite being in his minority.

Welsh incursion

In 1256, Roger’s cousin the Welsh prince Llewelyn ap Gruffydd invaded the Mortimer lands in Gwrtheyrion, sparking a long running conflict between the two houses that would continue for over 25 years. Skirmishes between the two lords became an ongoing feature of life in the Welsh Marches. For all the Mortimers’ castle building efforts, their castles did not prove particularly effective at stopping Welsh incursions. Llewelyn made significant gains against Roger, bypassing Knucklas to seize Knighton in 1260, and taking both Cefnllys and Knucklas after short sieges in 1262.

Second Barons War

Dissatisfaction with the leadership of King Henry III grew throughout the mid 13th century, as his exorbitant taxes combined with famine increased grievances among the barons, lead by Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester. Previously a royal favourite, Montfort had powerful ambitions of his own, marrying the King’s sister Eleanor without his permission. Roger Mortimer also joined the reforming group of barons. In 1258, Montfort’s faction forced the king to abolish absolute monarchy in the Provisions of Oxford. The provisions established a government council of leading barons and a parliament every three years. However, Henry was released from these obligations by the pope in 1261.

However, Henry had no intention of keeping his promises. Montfort lead the barons into rebellion in 1263, and fighting broke out in the Welsh Marches. Leading an army to London, Montfort captured the king and assumed control, though later released him following arbitration by the King of France. Montfort called for the cancellation of all baronial debts, which were owed to Jewish money lenders. To destroy evidence of debts, Montfort seized Jewish property and massacred Jews in a series of pogroms. Both the king and de Montfort then built up their armies in preparation for civil war.

Roger Mortimer, having rejoined the royal faction by 1259, became a loyal supporter of Henry, and played a leading role in the siege of Northampton in 1264. However, Henry III was defeated by Montfort at Lewes, where he was captured along with his son Prince Edward. Roger Mortimer was also captured but later restored to his position in the Welsh Marches. Despite his early victory, de Montfort suffered a series of reversals, as the Earl of Gloucester Gilbert de Clare deserted to the royalist faction. In 1265, Roger Mortimer helped Prince Edward escaped custody at Kenilworth Castle, who then proceeded to form a new army.

With the support of Roger Mortimer and the Marcher Lords, Edward attacked Montfort’s son Simon Montfort the younger, then besieging Kenilworth Castle. Simon de Montfort, having formed an alliance with Llewelyn ap Gruffydd, Prince of Wales, crossed the River Severn aiming to relieve the siege and link up with his son Simon’s forces.

The Battle of Evesham

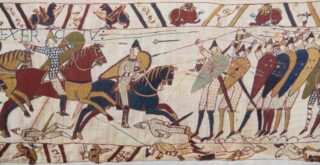

Montfort was forced into fighting Edward’s army at Evesham in 1265, after being backed into a corner within a bend of the river Avon. At ten thousand strong, Edward’s royalist forces were twice the size of de Montfort’s, and took the high ground in preparation for the battle. Roger Mortimer seized the only bridge over the river to block Montfort’s escape route. A storm broke above them, as thunder punctuated the noise of the soldiers. Faced with an uphill struggle, de Montfort formed a wedge to try and drive through the opposing army, but was quickly surrounded and his Welsh allies fled. The battle then turned in to a massacre as de Montfort’s army was routed, and Montfort was killed in battle near the bridge. The royalists achieved an overwhelming victory, and Roger de Mortimer played a crucial role, by killing Simon de Montfort in single combat. The result was decisive and effectively ended resistance to royal authority.

Roger’s wife Maud wrote to him after the battle, asking for a gift in celebration of their victory. There were no flowers for Matilda, for she expected a present of a more grisly kind. As Mortimer killed Montfort, he was awarded the traitor’s severed head, and soon after, Maud received the gruesome package at Wigmore. The object took pride of decorative place at their banqueting hall, for Lady Maud had laid on a great feast for Roger Mortimer’s triumphant return.

The Invasion of Wales

King Edward followed an aggressive foreign policy. In 1275 Prince Llewelyn married Eleanor daughter of Simon de Montfort, and was Llewelyn was declared a rebel by the king. Edward moved into Wales with a large army joined by Roger Mortimer. Llewelyn promised to limit his authority to Gwynedd alone in the Treaty of Aberconwy. As a grandson of Llewelyn Fawr, Roger Mortimer gained Maelienydd. When a second Welsh rebellion broke out in 1282, Edward responded with a full scale invasion.

As one of the leading lords in the Welsh Marches, Roger Mortimer played an important role in the invasion, acting as one of Edward’s leading generals. Roger may even have been involved in the death of Llewelyn the Last in 1282. To subject Wales to English rule, Edward built a series of mighty castles to dominate the Welsh.

So it was that the Mortimers had reached the highest ranks of the nobility. Roger Mortimer died at Kingsland in 1282 and was buried in Wigmore Abbey. His epitaph praised him as ‘Roger the Pure’ and celebrated his conquests in Wales, which he ‘subjected to torment’. King Edward I lamented Mortimer’s death, and in a letter to his widow praised “his valour and fidelity, his long and praiseworthy services to the late king and to him.”

Continue to Chapter 4. Pride before a Fall – The career of the infamous Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March

Recent Comments