Life on the frontier

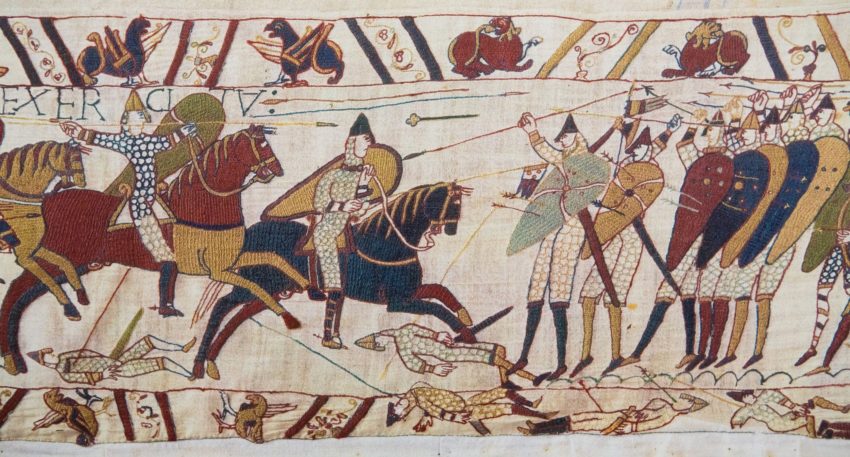

While the Mortimers of Wigmore were tearing through Wales as part of King Edward’s invasion of the late 13th century, another branch of the Mortimers had taken up residence in the far West of Welsh lands. This was an area settled by many such Marcher families, so beginning the annexation of Pembrokeshire which is reflected in a language border that can still be observed. The Mortimers gained an estate called Coedmore near Cardigan, building their chief residence at the New House, Coedmore. This branch of the Mortimers have male line descendants who continue to live in Wales to this day, one of the few Mortimer families who can definitively trace their heritage back to the Middle Ages. Moving west from Herefordshire, the Anglo-Norman Mortimers of Coedmore eventually naturalised as Welsh, intermarrying with Welsh families, choosing Welsh names for their children, and adopting the Welsh language.

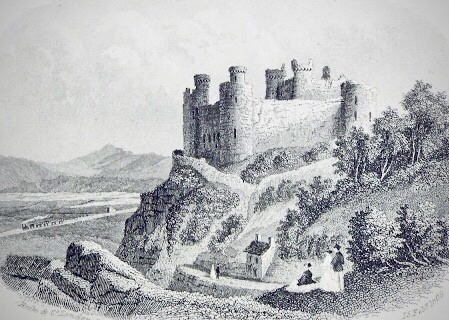

Coedmore is now an estate in the parish of Llangoedmor, Cardiganshire, and the place name originally means Great Wood in old Welsh, from “mawr” large and “coed” – a wood or forest. The Coedmore estate is overlooked by the magnificent ruins of Cilgerran castle, which was rebuilt in stone by William Marshal, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, son of the famous knight Sir William Marshall (1147-1219). Ralph Mortimer served in the first Earl Marshall’s household, and was evidently granted land for his feudal service. The Coedmore Mortimers took an active role in local affairs, and were successive constables of Cardigan castle. The associated between the Mortimers and Earl Marshall is reflected in the close proximity of Coedmore and Cilgerran. Coedmore was rebuilt in the 1700s and is now a hotel, while Cilgerran castle is owned by the National Trust and indeed well worth a visit.

The ancestor of the Mortimers of West Wales was Henry Mortimer, whose life remains shadowy. In 1241/2, Henry Mortimer was owed a debt by the heirs of Amauri de St Amand for lands in Herefordshire and Wales. Later, the Wigmore cartulary recorded that the bishop of St David’s granted to Sir Roger son of Henry son of Henry de Mortemer lands in Lyspraust and Isheylyn, which were probably in Wales somewhere. Henry would have been a younger son, but was unrecorded in the family chronicle of Wigmore Abbey, Fundatorum Historia, written in the 13th century.

The connection between the Wigmore Mortimers and the Mortimers of Cardigan, Wales was later affirmed sometime around 1290, when Maud widow of Roger de Mortimer released a portion of her dower lands to Roger Mortimer of West Wales, presumably son of the above Henry. In 1330, this Roger’s grandson Roger Mortimer of Coedmore was named within a petition as a “kinsman” of the Earl of March.

The arms of the two families of Mortimers, those of Wigmore and Coedmore, differ remarkably. The Mortimer of Coedmore arms were variously described as two lions rampant armed and langued, with the colours of the field and charges differing by source. However, difference in heraldry during this time period should not be taken as supporting no connection between the families, as many such armigers changed their coats of arms in the 13th century, including the Mortimers of Bec, who were related to the Mortimers of Richard’s Castle.

Roger Mortimer of West Wales was given land in the commote of Gene’r-Glyn, confirmed by royal charter in 1284. He lived at Is Coed Is Herwen, now known as Coedmore, in a residence known as the New House. He was said in some sources to have been a constable of Newcastle Emlyn Castle and fought against Rhys ap Maredudd as one of Tibetot’s officers. [This is worth researching further]

Roger married a Welsh lady called Nest, and had a son Llewelyn who succeeded him, the first Mortimer to be given a Welsh name. Llewelyn was perhaps a younger son, whose older brother predeceased his father. He was brought up with a mixed identity and presumably learnt Welsh from his mother. Llewelyn arguably inherited a joint Norman English and Welsh identity, common to many who were descended from the conquerors of Wales. English nobles settled Wales following defeat of the last Welsh Prince Llewelyn and subjugation of the Welsh by Edward I. Llewelyn sold the estate at Gene’r-Glyn to Geoffrey Clement. The family home would later become the New House at Coedmore

Coedmore was ultimately only acquired by the Mortimers through slight of hand, which details are recorded in a charter dated 1330. Originally leased to Roger Mortimer for life, after Roger’s death his heir Llewelyn Mortimer took possession of Coedmore and barred the original leasor’s heirs from entering. He sold half the moiety to Hugh de Cressingham, clerk of the king, and upon his death Coedmore reverted to the crown. The apparent original heir Eynon ap Gwilym sued and obtained writ of inquiry to the Justice of Wales in 1313, but Sir Roger Mortimer of Wigmore was Justiciar and apparently refused him justice, granting the estate instead to his “kinsman” Roger Mortimer.

A main source for assessing the ancestry of the Mortimers of Wales is the Heraldic Visitation of 1588, compiled by Lewis Dwynn. However, because it was made so long after the early individuals in the family tree had lived, and by that time many historical records had already been lost, several mistakes were made in the genealogy which now have proved very difficult to disentangle. These include missing generations, incorrect names, confusion between multiple individuals of the same name and confusion of spouses. References must be made to individuals who appear in the pedigree, whose floriat can be accurately determined. Only then will it be possible to pin down which generation married which partner.

The Mortimers of Coedmore had less wealth and power than the main line of Mortimers of Wigmore. It seems Roger Mortimer, aforementioned kinsman of the 1st Earl of March, was a missing link in the Visitation pedigree compiled in 1588. He had a son, Edmund Mortimer, who’s heir was Roger Mortimer.

The younger Roger Mortimer was probably born in 1350, and owned Coedmore in 1383, when he acquired letters of protection to serve in the Calais garrison. References to his life are sparing. In 1396 he witnessed a gift of land in Cardigan, and served as Mayor of Cardigan in 1418, assuming it was the same Roger after a gap of nearly twenty years. He died in 1424, at which point he held half a knight’s fee in Coedmore. Roger was succeeded by his son Owain Mortimer.

Owain was probably born in the 1380s, or slightly later. He served as a man at arms in the Agincourt campaign of 1415, in the company of John ap Rhys. Like his father, he went on to serve as mayor of Cardigan three times from 1421. Evidently enjoying success as mayor, he was made Constable of Cardigan in 1441. He received a pardon for all offences committed in 1446, and leased the lordship and manor in 1454 to William Rede, clerk.

After Owain Mortimer, the 1588 pedigree loses its way and becomes unintelligible. Owain likely died around the mid 15th century, after which point there was another thirty years before the next evidence emerges of Mortimers active in Cardiganshire. Richard Mortimer, alleged son of Owain according to the pedigree, was mayor of Cardigan in 1480, and his children were also born around this time. Richard himself was probably born around or after the time of Owain’s death when he was already old, meaning there is another gap in the generations. Richard was obviously related to Owain, but was more likely a grandson, whose father perhaps predeceased Owain Mortimer, which might explain why such an individual is missing from the pedigree.

Unfortunately, the following generation is also hard to determine. Richard married firstly to Margaret daughter of Owain ap Rhys and had two sons, James and John. John was mayor of Cardigan in 1525, and died before 1542, fathering two daughters.

Richard married secondly Elizabeth daughter of Griffith ap Owain. In 1503, he made a settlement on his second wife, perhaps to guarantee her property after the children from his first marriage inherited.

James Mortimer was lord of Coedmore in 1542. He married Elizabeth, daughter of Rydderch ap Rhys, lord of Towyn (fl. 1483-1515). James might have been son of John Mortimer, d. bef.1542, and his eldest son was John, which might support the suggestion. If James was the eldest son of Richard, he would have been very old when he died, perhaps 80 years old.

John Mortimer of Coedmore (c.1525-1596)

James Mortimer’s son and heir John was probably born around 1525, and became Sheriff of Cardiganshire in 1576. He married Eva Lewis, daughter of Lewis ap David Maredydd, and they had at least eleven children:

1. Ellen c.1552

2. Richard Mortimer c.1554-1609

3. Elizabeth c.1556

4. David Mortimer c.1558-c.1605, who in 1584 held a lease of land in Castle Maelgwyn. He married Ann Thomas, daughter of William ap Thomas and they had seven sons:

i. John c.1580

ii. Roger Mortimer of Llechryd, gent., c.1581-aft.1609

iii. Richard c.1582

iv. Thomas Mortimer, of St. David’s c.1584- , who had two sons:

1. Edmund Mortimer of St. David’s, gent., c.1608-1666, who had the following children:

i. Thomas Mortimer c.1645, named after his grandfather.

ii. Lettice c.1650

iii. James Mortimer c.1655, named after his uncle

iv. Mary c.1656

v. Benjamin c.1659

2. James Mortimer c.1610-aft.1666

v. William c.1586, who probably married Lleukie Harvey and had issue Ann and James.

vi. George c.1590

vii. Rowland c.1592

5. Thomas Mortimer c.1559-c.1602

6. Joan c.1560

7. Pernel c.1561

8. Philip Mortimer c.1562

9. Mary c.1564

10. Owen Mortimer c.1566-1638

11. Ann c.1567

Richard Mortimer (c.1554-1609)

Richard was mayor of Cardigan in 1602. He married Catherine daughter of Rowland Meyrick, Bishop of Bangor. They had children James, Rowland, John and Lettice. Both James and John appear to have died before 1613, and Rowland inherited Coedmore.

Later generations

Rowland Mortimer married Cecil daughter of James Lewis of Abernant, 20 Mar 1617, and in that year sold Coedmore to his brother in law John Lewis. Rowland and Cecil has a son John Mortimer, of Laugharne, who married Catherine Pugh. Their son was Rowland Mortimer (c.1646-1691). He married Rachel and had sons Roger and John. Roger married another Rachel and their only child and heir was Jane Mortimer, c.1697. Many descendants of the Mortimers are living today, including through the younger sons of John Mortimer d.1596).

Recent Comments