Legacy

On 14 October 2016, thousands of people gathered in a field near Battle Abbey, Sussex. They had come to celebrate a re-enactment of the famous Battle of Hastings, one of the few dates that everyone can remember from the history books, 1066 – the year English history began! Or so it would seem from the collective national consciousness. England in fact had a proud history as a united kingdom, going back nearly 150 years before Hastings.

However by 1064, England had become entangled in national turmoil, as the ailing King Edward the Confessor was increasingly frail with no descendants to continue his legacy. To make matters worse, the kingdom was beset by foreign enemies, as jealous onlookers sought to steal the nation’s wealth and take advantage of the impending dearth of English unity. Across the North Sea were the Anglo-Saxons’ old foe, the Danes, who had invaded England many times over. The Welsh, Scots and Irish were emboldened by the waning of England’s defences, while restless powers in Normandy dreamed of conquering a new prize. Complicating the matter further, King Edward had family ties to both ruling houses in Denmark and Normandy. His mother Emma of Normandy had remarried to Edward’s predecessor King Canute, the Danish-born ruler of England, Denmark and Norway. King Edward had a close connection to Normandy through his mother’s family and had spent years in exile there before his own accession to the throne. Throughout his reign Edward embarked on a Normanisation of England bringing in many Norman advisers, clerics and courtiers.

Rise of the Godwins

Though Edward had a natural heir in his great nephew Edgar the Aetheling, Edgar was young and ill-equipped to deal with the numerous threats to English sovereignty. To this end stepped up the king’s brother in law Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, the second most powerful figure in the land. A capable military leader, Harold was imbued with confidence following victory over the Welsh and Gruffydd ap Llewelyn in 1063. What young Edgar lacked, Harold possessed in spades- vast wealth, courtly influence, and universal respect among peers. If anyone was to guard England’s interests and defend against growing Norman influence at court, it would be Earl Harold.

Harold was born circa 1022 into a noble family, the son of Godwin, Earl of Wessex. As a powerful noble, his father had close ties to the previous regime of Canute, and conspired in the death of Edward’s brother Alfred Aetheling in the chaotic reign of Cnut’s son Harthacnut. Godwin had such influence that he acted as king maker in the succession of Edward in 1042, and arranged the hand in marriage of his daughter, Edith. They had no children and Edward harboured lingering resentment to the Godwins, banishing them in 1051. It was only through force of arms that Godwin compelled Edward to restore their estates. In such a malaise, Harold succeeded to the Earldom in 1053, making him an influential political figure.

Harold and his wife Edith Swann Hnesce or “gentle swan” were married in the Danish manner, as befitting the custom of the time. He earned his stripes in battles against Magnus king of Norway, and drove back the Welsh from Herefordshire, eventually defeating king Gruffydd ap Llewellyn in 1063. His star was clearly rising, and it would not be long before Harold controlled all England.

A mysterious voyage

It is quite unknown how Harold ended washed up on the coast of Ponthieu in 1064, but he had presumably sailed from Sussex on a mission shrouded in secrecy. He had the misfortune of being blown off course and shipwrecked, then captured and held hostage by Guy Count of Ponthieu. Ten years previous, Guy had lost against Normandy in the battle of Mortemer, 1054. As Normandy’s vassal, he handed over Harold to the Norman duke William, who seemingly treated him well. Harold joined the duke’s retinue and fought for William against his rival Conan, Duke of Brittany. The campaign was successful and Harold was knighted by him, having saved two of his men from the perils of quicksand near Mont St Michel. The two nobles struck an agreement and parted ways, though the substance of such a bargain remains a matter of great contention. The Normans maintained that Harold swore an oath of fealty to Duke William and supported his claim to the English throne, in apparent fulfillment of a promise by Edward the Confessor. If the king had made such a promise, he truly had lost his marbles, for it was the Witenaġemot, or counsel of eoldermen, that decided on the English kingship. It was certainly not the place of either Harold or any other noble to promise the crown to William.

Harold’s younger brother Tostig became Earl of Northumbria, though was deeply unpopular. Considering the threat from William, Harold was forced to exile him in 1065 to ensure loyalty in the north. Tostig grew bitterly resentful of Harold and plotted vengeance, scheming to overthrow him with the help of Baldwin Count of Flanders. The following year, Tostig raided the coast and invaded England, though was forced to retreat to Scotland. He would later lend his support to the Norse.

Succession

The passing of a monarch in medieval Europe was always a momentous event, though in the case of England in 1066 the stakes were higher than ever. As king Edward the Confessor lay on his death bed, he commended the kingdom to his widow Edith, and entrusted the nation’s protection to his then reconciled brother in law Harold Godwinson. King Edward died on 5 January, and power shifted rapidly to Earl Harold. Confirmed king by Witan convened the following morning, Harold was crowned, perhaps at Westminster. Knowing that William of Normandy had designs on his kingdom, he rapidly moved to consolidate power and prepare England’s defences. William immediately planned to invade following news of Harold’s succession, preparing a fleet of over seven hundred ships. When Harold discovered William’s plans he levied an army to counter the threat, but was forced to disband troops when the invasion did not immediately materialise. In April Halley’s comet appeared in the sky, marking an omen of change, the comet became associated with England’s succession crisis.

The Norman fleet was forced back through bad weather, and the first threat came instead from king Harald Hardrada of Norway, convinced by Tostig to invade England. In September 1066 Harald’s invasion fleet of 300 ships sailed up the Humber. It was at Fulford, Yorkshire that the invaders clashed in battle with English earls Edwin and Morcar, where the English forces suffered defeat. Harold Godwinson was forced to mobilise his troops, including an elite force of huscarls. In only four days, the king marched his army up the old Roman road of Ermine Street to York, surprising the invaders at Stamford Bridge. Many of the Norwegian forces had stayed behind to guard the fleet, and some were without armour. Harald’s forces retreated across the bridge, where a single Norse axeman held up the advance of the English before being slain. The Norse made a shield wall and the English outflanked them and charged. The fighting was intense and lasted most of the day, though the English won a complete victory. Both Harald Hardada and Tostig were killed and the Norse army virtually extinguished. Harold accepted a surrender from the remaining Norwegians, and the survivors sailed away in only 24 ships.

Hastings

William of Normandy’s original invasion fleet was blown off course by bad weather. King Harold had in response summoned the fyrd, an Anglo Saxon fighting force of landowners. William’s fleet of over 700 ships sailed in September and landed at Pevensey. The Normans fortified their position and sacked local settlements. Such an invasion could not have come at a worse time for Harold, who was travelling down to London after fighting the Norwegians, having left many forces in the north, including the Earls Morcar and Edwin. Harold’s army hurried south averaging 27 miles a day. Tired from the exertion, the English encamped near Hastings. All overtures of diplomacy failed and the two armies seemed destined to meet on the field of battle. Both forces had over 7,000 men, though Harold’s army was infantry while the Norman’s were composed of infantry, cavalry and archers. Harold’s brothers Gyrth and Leofwine were loyal to him and would fight alongside him.

On the day of confrontation, Harold deployed his troops in a dense formation atop a steep slope, with the flanks protected by woodland. To attack, the Normans were forced to cross marshy land in front of them, though the Anglo Saxons had no archers to take advantage of the slope. In response, William divided his forces into three groups, the Bretons, Normans, and French, taking charge the Norman division personally. Alan the Red commanded the Bretons while William FitzOsbern ordered the French.

The battle commenced with the Norman archers firing at the English infantry, though the defenders formed a shield wall and the arrows had little effect. After running out of arrows, the Norman spearmen advanced uphill, and were caught off-guard by a volley of spears. The two sides clashed, and the English shield wall held strong against the Normans. The battle continued in such vein for some time, before a lull in the fighting. Failing to gain advantage, the Norman forces withdrew from battle temporarily.

Hoping to force a path through the opposing infantry, William commanded a frontal cavalry charge against the defensive line. In the general melee that ensued the English resisted the Norman assault manfully, while fighting the attackers back with vigour. The Normans were losing men and ground, as the Anglo Saxons took confidence from their excellent position. Harold’s army was gaining the upper hand, and the Normans began to retreat, beginning with the Breton flank. Duke William had no less than two horses killed from under him, and was forced to retreat on several occasions. Around the battlefield there were cries that William had been killed, and Norman soldiers and mounted knights fell back in disarray. The defending English pursued in earnest, though Harold ordered his men to stand ground. Despite the order, many of the English followed the Normans, perhaps lead by Harold’s brothers Gyrth and Leofwine.

It was at this point that William lifted up his helmet to show he was alive, and rallied the Normans around him. The English in their rush down the hillside had lost their defensive formation and suffered terribly against the renewed Norman charge. Gyrth and Leofwine fell in the fighting, and Harold was eventually surrounded, protected only by his elite guard of huscarls. Harold fell in battle against the Normans. Seeing the death of

- The earliest records mention only that Harold was killed in the battle. His body was mutilated but was later identified by Harold’s fair widow Edith, who recognised his body by “certain marks familiar only to her”. This suggests that Harold was killed in a melee combat. The story of Harold being killed by an arrow appears only later, by a writer who had neither first hand knowledge or experience of the battle. Crucially this was after the creation of the Bayeux Tapestry.

- Harold apparently went back on his word to William according to the Normans, having promised William the throne in the succession of the Kingdom of England. This was the main justification given for the Norman conquest of England. For a long time before this period in the Middle Ages the punishment for dishonesty was to lose an eye. Therefore it’s hardly surprising that later chronicles might attempt to revise history to say that Harold was killed by an arrow in the eye, which would be interpreted as divine punishment and reinforce William’s right to rule.

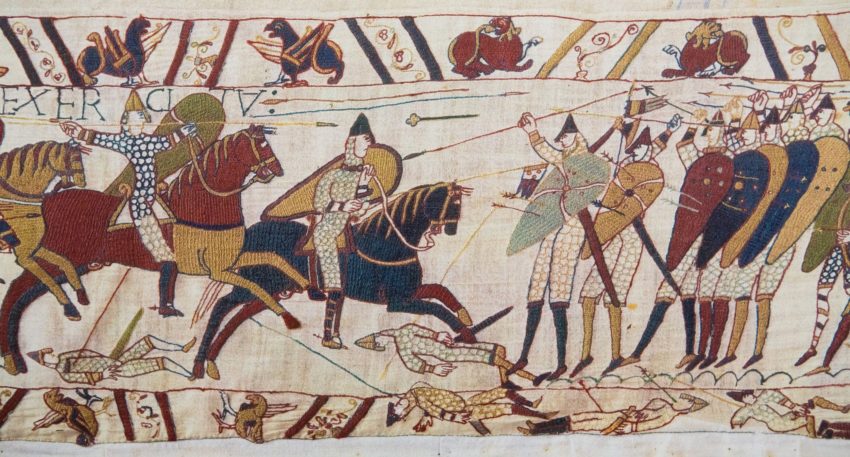

- One of the main sources of evidence cited in support of Harold being killed by an arrow is the Bayeux Tapestry. As a detailed illustration created soon after the Battle of Hastings, it is seen as an important near contemporary source of information for the events of the Norman invasion. A closer inspection of the tapestry reveals that the illustrated narrative does indeed support the earliest historical records of the battle. At the part of Harold’s death, the tapestry reads Harold Rex Interfectus Est. (King Harold has been killed). Below the second part of the writing the tapestry shows a Saxon fighter being killed by a mounted Norman knight.

- To the left of this warrior’s death, there is a soldier who it seems is struck by an arrow in the head. This figure can be clearly identified as a Saxon. The word Harold appears immediately above his head which for a long time has been assumed in support of identifying the man as Harold, king of England. However, the writing does not conclusively identify the individual as Harold. In many other places in the tapestry, writing refers to events taking place in the tapestry not immediately below the writing, and this is quite reasonably the case here. This is especially so if the Saxon on the left is not shown as being killed.

- The Bayeux tapestry as we see it today was restored in the 18th century. Sketches of the tapestry before the restoration do not show the arrow, and as such it is the result of a later alteration. The most likely interpretation is the Saxon soldier was carrying a spear. During the restoration the spear was partly removed and fletching added to form an arrow. This was done to align the tapestry to the arrow story which by that time was widely accepted. Upon close inspection of the tapestry this is still obvious today, as the line of the arrow angles over the top of the victim’s heard. Once the support for the arrow from the Bayeux tapestry can be discarded, the majority of supporting evidence for the above assertion falls away.

- Friendly fire? In the tapestry, Harold is killed in a brutal melee at a point nearing the end of the battle, after the battle turned in favour of the Normans. By this point the Normans had carried out several charges and pressed the Saxon defence to breaking point. Once the melee had begun, the Normans would not have fired arrows at their own knights or their leader Duke William, who was heavily involved in the throng of fighting. Research suggests the tapestry is an accurate depiction of contemporary warfare and is corroborated by archaeological findings.

- The Saxons fought in a shield wall, a technique long practiced by the Saxon peoples, and originally created in antiquity. To form the wall each soldier would hold up their shield and raise their spear, and would initiate this formation at the prospect of a cavalry charge. A close look at the tapestry in this scene shows that the soldier hit by an arrow is holding arm in the same position as the soldier to the left of him who is carrying a spear.

- The angle of the supposed arrow hitting the Saxon in the head is completely wrong and on reflection, has always seemed a bit strange. During a battle, archers would engage the enemy army by firing a volley into the mass of opposing troops, angling their bows upwards. This means arrows would rain down on the unfortunate victims from above. The arrow would not have hitting Harold at such an angle unless the archer was lying on the ground in front of him!

So it is that the myth of an arrow in the eye was born.

Recent Comments